Florida’s prison system, overrun with violent gangs distributing contraband, operating rackets, running shakedowns and carrying out blood feuds, is looking to create a separate category of incarceration where those seen as the worst troublemakers can be bunched together, segregated from the rest of the general population.

This prison-within-a-prison would be referred to as an administration management unit, or AMU.

The Florida Department of Corrections says it is a way to operate the system more safely while critics say it is an attempt to impose a major change while everyone is focused on the COVID-19 pandemic.

Under the newly proposed rule, as few as two serious disciplinary reports — or DRs — could result in an inmate being placed in an administrative management unit. First there would be a quasi-judicial disciplinary hearing for which the inmate would be given 48 hours notice.

After collecting the facts, the prison would make a recommendation to the central FDC office, which would make the final call.

Prison employees have extraordinary leeway to write up disciplinary reports for real or imagined transgressions. For instance, kicking a cell door or complaining loudly can be deemed “inciting a riot,” which could be cause for being relegated to an AMU.

That leeway has long been an issue in the Florida prison system, where inmates can be punished by limiting their exercise, visitors, use of a telephone, shower access and possessions such as books, photos, writing instruments, tablets and access to the canteen. “Confinement,” a restrictive form of incarceration, is referred to by prison inmates as being in jail.

The latest proposed rule change was first announced on March 25, 2020, when the number of COVID-19 cases in Florida was nearly 2,000. The first corrections officer was reported to have tested positive just the day before.

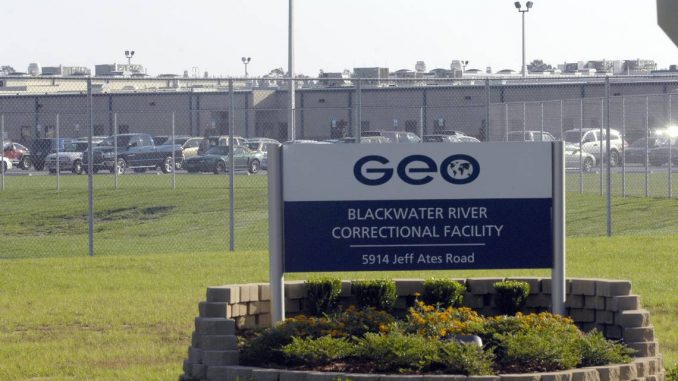

The proposed rule was made public on April 10 — the same week that FDC saw its first coronavirus-related deaths — Jeffrey Sand and William Wilson, both inmates of privately managed Blackwater River Correctional Facility in Santa Rosa County. FDC did not release information about their deaths for six days and acknowledged them only after The News Service of Florida reported them.

The number of COVID-19 positives in prison has since grown to 393 inmates and 180 staff members, despite fewer than 1 percent of inmates being tested. Seven inmates have died.

New rules have to go through formal procedures before they can be implemented. A draft proposal is first published and opened to public comments. In the event of strong objections, a hearing is held before the Joint Administrative Procedures Committee, an oversight body of state lawmakers, which decides whether to green-light the rule.

New head of Florida prisons sees dire warning signs. ‘Status quo is not sustainable’

One of the most recent proposed rule changes was one to cut visitation privileges in half in conjunction with the state making tablets available for sale to inmates. The proposed change ignited a storm of criticism. Prisoners’ friends and relatives drove in from all parts of the state to attend a hearing and the FDC backed down.

Kelly Knapp, an attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center, said the criteria for placing inmates in the AMU are “vague and broad” and even keep open the possibility that they can be applied retroactively, before the existence of the units.

There are already various ways to classify inmates, with inmates who cause trouble sometimes being placed into one of three tiers of what the FDC calls “close management.” In the strictest tier, inmates are allowed visitation or to make a phone call every 30 days, only after initially completing the same number of days with no visitors. In the other two tiers, the same initial 30-day period applies, but subsequently inmates can receive visitors or make a call every two weeks.

The new rule, as proposed, says individuals placed in an AMU will “have access to the same privileges” as other general population inmates. Except during the current pandemic, inmates can receive visitors every Saturday and Sunday from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m..

The new rule, however, would restrict visitation for those in the new AMU units to only two hours every 14 days. This cut is exactly the same as the previously proposed one that the FDC backed down from.

Placement in an AMU would be reviewed at least once a year.

“If this population is already difficult to manage, denying them family visits and community support that are vital for rehabilitation is counterproductive,” said the SPLC’s Knapp.

Karen Smith, an activist with the Florida chapter of the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, said that “the state is trying to get this rule passed quietly while people are distracted by the COVID crisis” and that she is unsure what a public hearing on the issue would look like with social distancing in place.

The FDC in a statement to the Miami Herald said that the rule had been in development since summer 2019 and is not related to COVID-19 in any way.

“All regular procedures and protocols with the implementation of this rule will be followed,” the department said. “FDC will honor all requests for a public hearing.”

The proposal suggests that the creation of separate AMU units — to house those who display an “inability to live within an institutionalized setting without abusing the rights and privileges of others” — is aimed at curbing gang activity inside the state’s prison system.

The state’s prison system — the third largest in the country — has been grappling with gang violence for years.

According to the latest FDC annual report, Florida’s prisons house nearly 12,300 inmates who are affiliated to more than a thousand nationally known and local street gangs. A majority of them are convicted of murder, manslaughter, robbery or burglary.

James V. Cook, a Florida civil rights lawyer who deals with issues of prison abuse, penned an op-ed in the Herald in February 2020 where he detailed how understaffed corrections authorities turn a blind eye while gangs virtually run certain sections of prisons, move drugs and collect for nonpayment in blood.

“Concentrating this population into one or more facilities will allow FDC to more efficiently and effectively direct resources and maximize security oversight,” said the FDC. “Simultaneously, the strategy will remove disorderly inmates from other institutions.”

Once implemented, one facility will be chosen to pilot the new rule before it is extended to other correctional institutions.

The proposed rule would apply only to inmates who are classified under “general population” — those who can socialize with others and are not given any specific treatment.

The FDC said that it hopes to reduce the number of inmates in close management with the implementation of AMUs.

Last year, six inmates filed a class-action lawsuit against the FDC challenging the department’s use of all forms of solitary confinement as cruel and unusual punishment.

A 2018 report by the Southern Poverty Law Center stated that solitary confinement, including those under close management, was disproportionately applied to black inmates and inmates with mental health issues and also is a waste of taxpayers’ money.

Inmates can be placed in close management if they commit acts of rioting, assault another individual, smuggle prohibited substances or are found to possess tools for escape. A panel consisting of prison officials assigns the level of punishment depending on the degree of the offense.

The department stated that AMUs will serve as “highly structured environments” designed “to separate inmates within the general population, due to their own actions, but do not meet the threshold for close management.” Similar to close management, inmates in AMUs will also be allowed to keep their books, writing materials and tablets.

FDC said, unlike certain categories of close management, inmates in AMUs will not be placed in single cells. The new rule also does not have any condition that would result in AMU inmates having exercise schedules or opportunities that are different from those enjoyed by the general population.

“The key to increasing public safety is to provide people with behavior problems the tools they need to live with all different types of people, not to concentrate and wall them off until they are released back to their communities completely unequipped to manage the challenges of living in an integrated society,” said the SPLC’s Knapp.

The draft proposal — unlike the rules for close management — does not make any mention of extra resources being directed to those housed in AMUs to increase their chances of rehabilitation.

On a conference call hosted by Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM), which has expanded its portfolio beyond prison sentencing reforms, Florida advocate Denise Rock expressed her concern that instead of creating a rehabilitative environment, the new units would be places “where you would throw the bad people.”

Rock said the decreased visitation could make behavior worse. Drug use and violence often stems from a lack of familial support, she said.

“Families would prefer to see a place for people struggling with drugs or gang involvement,” she said. “Those people should be getting extra attention, not less.”

On the call, state Sen. Jeff Brandes, R-St. Petersburg, said he sees the units as more of an incentive program that could change behavior.

Brandes, vice chairman of the Senate’s Criminal Justice Committee, told the Miami Herald that it shows FDC Secretary Mark Inch acting within his scope and authority to improve upon a model he inherited when he was appointed to the role last year.

“He is recognizing that he can build a better incentive-based model within the prison system and he doesn’t need legislative authority to do that,” Brandes said. “Incentives can help drive behavior and can both reward and punish behavior inside the correctional facilities.”

*story by Miami Herald