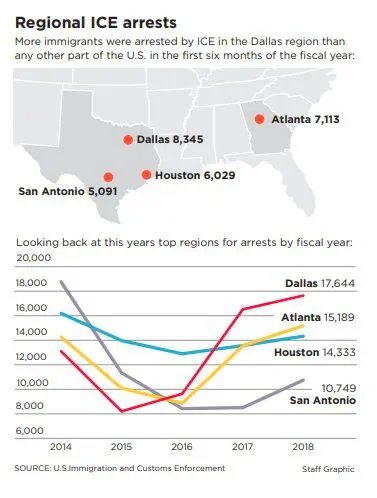

More immigrants in North Texas have been arrested by federal immigration officials in recent years than any other region of the U.S.

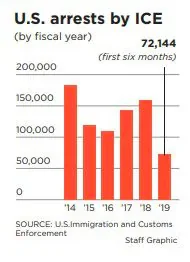

In fiscal year 2015, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, arrested about 8,000 immigrants in the sprawling region, which covers half the state and Oklahoma. Last fiscal year, the number more than doubled to about 17,600. In the first six months of this fiscal year, ICE has detained about 8,300, according to the agency.

Some say the relative strength of the economy and the strong job market are luring more immigrants to the area and their larger numbers are likely driving up the number of arrests. But others say the increase has come as Texas has stiffened its immigration enforcement resolve and California has pivoted toward limiting federal cooperation.

North Texas law enforcement officials are simply more friendly toward federal immigration enforcement than other parts of the state, says Randy Capps, director of research for U.S. programs at the D.C. -based Migration Policy Institute.

“They have very enthusiastic participation rates from local law enforcement,” said Capps, who studies arrests and deportations during the presidential administrations of Donald Trump, Barack Obama, George Bush and Bill Clinton.

At the Dallas office of ICE, Marc J. Moore, the field office director for enforcement and removal operations, agreed that cooperation by local officials has boosted results in his Texas region.

“North Texas is really blessed with great collaboration with local law enforcement agencies,” Moore said.

About 70 percent of ICE arrests come after the federal agency is notified by local jails or state prisons, ICE acting director Matthew Albence said last month.

Sanctuary cities law

Under the “sanctuary cities” law passed as Senate Bill 4 by the legislature in 2017, all jails have to honor detainer requests. Intentionally failing to honor a detainer can subject the jailer or law enforcement agency to civil penalties that escalate up from not less than $1,000 for the first violation and not less than $25,000 for each subsequent violation.

A “local entity” found by a court of law to have intentionally violated the law can also be subject to those escalating civil penalties.

The law, also known as the “Show me your papers” law, is being challenged in the courts by Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, but major parts — including the detainer requirements — are in effect as the case moves through the courts.

“My general sense of things is that most county jails were complying with detainers,” said Nina Perales, MALDEF’s vice president for litigation. “They have to comply now. “

In Texas under the new law, local law enforcement officers also can question the immigration status of people they detain or arrest, but they aren’t required to do so.

Moore, the regional detention official for ICE for the last year, downplayed the effects of the “sanctuary cities” law. “Certainly SB4 may provide some small amount of help,” he said.

Moore instead praised Dallas County for access it provides for ICE staff. The Dallas County jail can hold about 7,100 people, making it one of the nation’s largest jails.

“We certainly are not hamstrung there in our ability to work with the sheriff’s department and identify individuals that have criminal convictions or pending criminal charges,” Moore said.

That’s not the case in some other parts of the nation.

The detainers at the heart of the arrests are a key tool of ICE’s Secure Communities program, which rolled out across the nation more than a decade ago. The program signaled a sea change in the way ICE operated because Secure Communities linked databases between the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security as background checks were made on immigrants.

In recent years, several states, including California, have limited their cooperation with the federal program. That’s prompted praise and condemnation. California has the nation’s largest unauthorized immigrant population. Several court challenges have questioned the constitutionality of the detainer holds and the quality of the databases used by the federal government.

A California federal court in late September issued a permanent injunction on the use of certain electronic databases for ICE detainers. Those electronic databases are widely used — but not in most of ICE regional offices in Texas, including Dallas, said lawyers for the National Immigrant Justice Center, one of the parties bringing the suit in California.

But the use of ICE detainers, or holds, on immigrants at local jails has been controversial. An ICE detainer is a written request that asks a law enforcement agency to detain individuals for an additional 48 hours after their scheduled release date. It allows ICE agents time to arrange transportation to take the individual into custody for deportation.

The detainers are mostly used on unauthorized immigrants, but under federal immigration law, legal immigrants are also eligible for deportation if they run afoul of the law.

Busy Mexican consulate

Though net migration from Mexico is down nationally, there’s still growth in North Texas, where the economy is bubbling. The Mexican consulate in Dallas is working extended hours to help families caught in the federal enforcement net, said Francisco de la Torre, the Mexican consul based here.

De la Torre called growth of Mexican migration to North Texas strong and said his office has doubled staff in its protection unit, which helps immigrants with legal matters. But he didn’t criticize ICE for its role in creating that work.

“They have work to do,” said de la Torre of ICE. “We have work to do. We are not enemies.”

(snip)

The Dallas region leads in the number of ICE arrests but that doesn’t mean it leads in deportations. The San Antonio regional ICE office outdistanced many others with 62,000 deportations last fiscal year. By comparison, the Dallas regional ICE office had about 15,000.

And overall, former President Barack Obama still leads in the number of deportations during his administration, despite the fact that immigration has become the signature issue of President Donald Trump. That earned Obama the name “Deporter in Chief,” a title Trump has yet to take.

*see full story by Dallas Morning News