(Bloomberg) — Terms of Trade is a daily newsletter that untangles a world embroiled in trade wars. Sign up here.

German banks are stuffing vaults with money to help offset the mounting cost of negative interest rates, and some of them are running out of space.

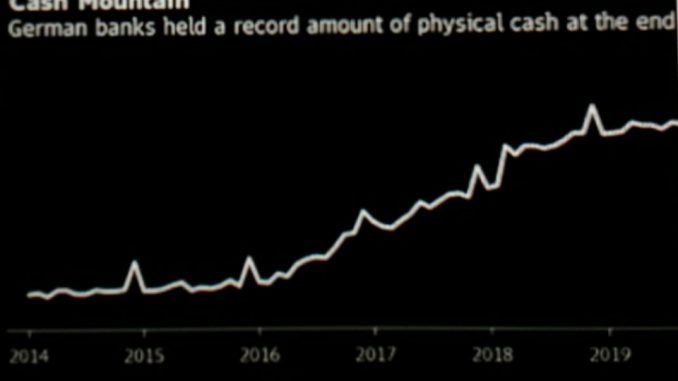

The physical cash holdings of German banks rose to a record 43.4 billion euros ($48 billion) in December, according to Bundesbank data published on Friday. That’s almost triple the amount at the end of May 2014, the month before the European Central Bank started charging for deposits and raising the pressure on Germany’s already beleaguered banks.

As the economy weakened last year in the face of international trade disputes, the ECB pushed rates further below zero to stoke inflation in the euro area by making it even cheaper for companies and individuals to borrow. While lenders also benefit from growth, negative rates are a threat to German banks because they rely heavily on interest from loans and sit on a mountain of deposits.

“These days it’s better to keep funds in cash rather than park them at the ECB,” said Andreas Schulz, who runs a savings bank close to Berlin. “That’s despite the risk, insurance costs and logistical hassle involved. It’s a ludicrous demonstration of the consequences of the ECB’s interest-rate policy.”

Right now, there isn’t enough space for the cash that many banks want to hold. Pro Aurum, a Munich-based precious metals trader, received several requests from banks to store notes in its vaults. However, the firm had to turn them down because of a lack of capacity.

“The ECB’s negative interest rates make hoarding cash attractive,” said Frank Schaeffler, a German member of parliament with the opposition Free Democrats. “This is just the beginning. If it continues, we’ll see a boom for vault makers and security companies.”

Accepting deposits to fund loans is at the heart of banking, but European lenders are awash in liquidity and argue that they can’t pass it all on in the form of credit. That leaves them sitting on billions of euros they have to take to the ECB or find another solution for.

Holding more cash isn’t enough for a banking sector with about 3 trillion euros of deposits to escape the burden of negative rates. The Association of German Banks expects the ECB’s charges to cost the country’s lenders about 2 billion euros a year.

Deutsche Bank AG and Commerzbank AG, Germany’s biggest publicly-traded lenders, are are also contending with side effects of the ECB’s stimulus. The two firms are pursuing radical overhauls and cutting thousands of jobs after negative interest rates and the spread of digital technology upended their business models.

That includes passing on the charges for deposits to corporate and wealthy clients. However, it’s more complicated — and sometimes illegal — to apply the same policy to the broad mass of retail customers.

“We are managing our balance sheet in a more dynamic fashion to mitigate the drag from liquidity reserves,” Deutsche Bank Chief Executive Officer Christian Sewing said in December.

Germany is hit hard because its citizens save more than most other Europeans and avoid riskier products that earn banks fees. The country’s savings rate was around 10% in 2017, almost twice the euro-area average, according to Deutsche Bank economists. Last year, Germans held just 21% of their 6.6 trillion euros of financial assets in the form of investment funds, shares, certificates and bonds, according to DZ Bank AG.

The volume of notes that banks are squirreling away is small compared with the deposits they hold, but the trend is fuel for German critics of the ECB, who say negative rates are reaching their limits and not stimulating the economy as policy makers intended.

In the ECB’s defense, its own estimates show that without the central bank’s wider policy actions, real GDP in the euro area would have been as much as 2.7 percentage points lower at the end of 2018. The ECB has also hit back at German lenders’ criticism of its negative rates, saying that inefficient banks should focus on reducing costs rather than simply blaming accommodative monetary policy for their problems.

To be sure, the ECB has sought to limit the side effects of its negative rates by exempting a portion of deposits held at the central bank from the charges. That system, known as tiering, may have eased the pressure on banks, according to Cornelia Schulz, a spokeswoman for the Association of German Cooperative Banks. The group expects its members to have cut their combined cash holdings at the end of 2019 from previous years, she said.

Germans were already well known for their love of physical money and data privacy. Until 2017, cash accounted for more than half of all transactions, according to the Bundesbank. That may explain why lenders aren’t the only hoarders. Wealthy individuals are also increasingly resorting to cash, potentially to avoid charges at their banks.

“We’re seeing increased demand for our safe deposit boxes, frequently for storing cash,” said Markus Weiss, a managing director at Degussa Goldhandel. “That high demand has lasted for months now and we’re continuously expanding our capacities,” said Weiss, whose company sells gold and offers clients space to store their valuables.

*story by Bloomberg