(Bloomberg) — Coronavirus-induced market mayhem has pushed so much liquidity out of U.S. Treasuries that the true value of more than $50 trillion in assets around the globe is in doubt.

Yields in the world’s largest debt market have been on a mind-bending, three-week roller-coaster ride. At one point, the entire U.S. yield curve was below 1% for the first time ever. But this week rates have jumped from Monday’s all-time lows even though fear of the virus has intensified, and U.S. stocks sank into a bear market Wednesday. The biggest oil-price plunge since 1991 also stirred chaos this week.

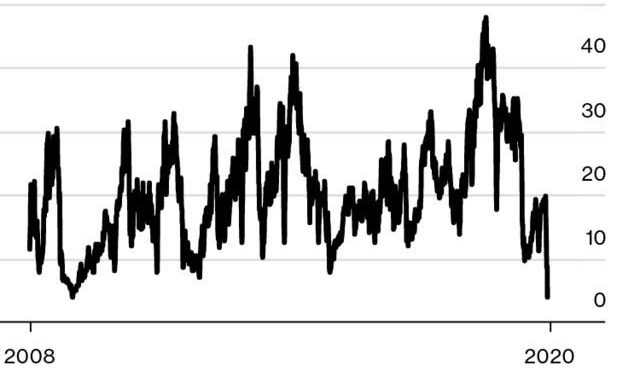

This volatility is happening as trading-platform order books thin out to a degree last seen during the 2008 financial crisis, making it harder to use Treasuries as a gauge of investor anxiety.

And that’s not just a problem for the bond market’s elite since rates on everything from mortgages to municipal bonds and emerging-market debt are pushed and pulled by U.S. yields.

“Treasuries are the risk-free benchmark that anchors the over-$50 trillion in global dollar-denominated fixed-income securities,” said Joshua Younger, head of U.S. interest rate derivatives strategy at JPMorgan Chase & Co.

“The level of volatility and lack of clarity in Treasuries makes it much harder to make sense of the value of all other assets,” added Younger, who has an astrophysics Ph.D. from Harvard University. “It can create a self-perpetuating flow of expectations that is not really reflective of financial markets and the true level of risk aversion.”

One key gauge of Treasury liquidity — market depth, or the ability to trade without substantially moving prices — has plunged to levels last seen during the 2008 financial crisis, according to data compiled by JPMorgan. That liquidity shortfall, JPMorgan says, is most profound in long-term Treasuries.

The ease of transacting in Treasuries is important for regulators as well. Liquidity drew greater scrutiny after Oct. 15, 2014, when Treasuries convulsed with no apparent trigger in what was dubbed a flash rally.

Following that mysterious move, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority began collecting transactions data in 2017 for regulators. Just this week, Finra for the first time began releasing aggregate weekly statistics to the public.

Amid the current liquidity shortage, the cost to trade Treasuries is spiking. In the interdealer market, about 66% of 30-year bond trades are taking place at wider-than-average bid/ask spreads, or the difference between prices to buy and sell, JPMorgan data show.

All that said, even though liquidity is scant, it’s still possible to cash out of Treasuries. Such selling could partly explain why yields have risen for two days.

Treasuries are the “only product with any semblance of liquidity,” said Bill Finan, senior managing trader at Columbia Threadneedle. “So to hedge, however inefficient the hedge, you sell rates.”

For Todd Colvin, senior vice president at Ambrosino Brothers, what has transpired since the beginning of March in the Treasury market is worse than what he experienced after Long-Term Capital Management blew up in the 1990s, requiring a bailout orchestrated by the Federal Reserve.

The hedge fund lost $4 billion in 1998 after Russia’s default prompted investors to shun corporate and mortgage-backed bonds and buy less risky, more easily traded government securities. The carnage drove yields on 30-year Treasuries to a 1990s low of 4.72% in October 1998, down from a 1997 peak of 7.17%.

This week, a Treasury rally on Monday produced the biggest intraday decline in 30-year yields since at least October 1998, when Bloomberg began recording daily highs and lows. The rate fell as much as 59 basis points to a record low 0.699%, its first-ever breach of 1%. Of the 10 steepest intraday declines, one occurred last week and four were in 2008 or 2009.

The 30-year yield, which sits around 1.24% Thursday, is down from this year’s high of 2.42% set in early January. The 10-year yield is at 0.74%, down from its 2020 peak of 1.94%.

The bond market was far smaller before the turn of the century. America’s debt pile has grown to nearly $17 trillion from about $2 trillion in 1990. Some think that can feed volatility.

“The ability for markets to move is greater because the size of the market is much bigger now,” Colvin said.

And back in the 1990s markets weren’t highly electronic like they are now. Back in those days, what happened in other markets around the globe didn’t hit as close to home. That’s changed with globalization.

Today, investors and economists are struggling to figure out the path of the global economy as well as monetary and fiscal policy amid the spread of the deadly virus. Coupled with the worst trading conditions since the great recession a decade ago, pricing Treasuries has become a nightmare.

“In a crisis you’re going to sell what you have, not what you want to,” said Priya Misra, rates strategist at TD Securities. “This is not a normal functioning market.”

*Story by Bloomberg