As unrest has continued into a fourth month in Portland, a detachment of Oregon state troopers specially deputized to act as federal law enforcement agents has been sent to the city to help keep order.

The move, first reported by freelance journalist Deborah Bloom, allows them to bring suspects to federal courts for arraignment and prosecution, circumventing local prosecutors who are seen by some law enforcement agencies as excessively lenient with demonstrators.

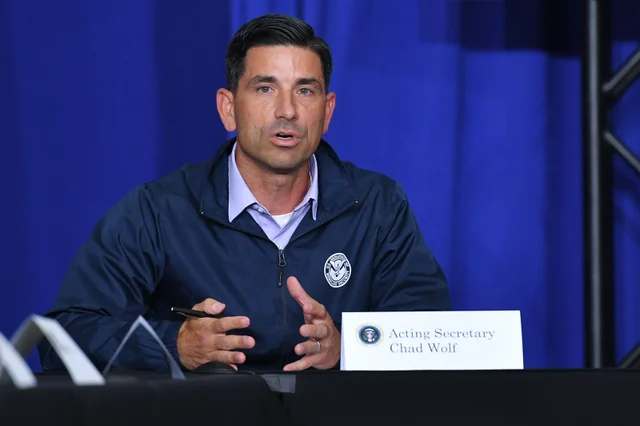

It comes as President Trump and acting Homeland Security Secretary Chad Wolf are again considering deploying federal officers from various departments to Portland following escalating clashes among pro-Trump activists, armed militants and left-wing demonstrators, which turned deadly last weekend. But the initiative for deputizing state troopers didn’t come from the DHS or the White House — it appears instead to reflect frustration on the part of Oregon State Police with a policy issued last month by Multnomah County District Attorney Mike Schmidt on how to prosecute protest-related offenses.

An OSP spokesperson said: “OSP is not criticizing any officials and we respect the authority of the District Attorney, but to meet the Governor’s charge of bringing violence to an end we will use all lawful methods at our disposal.”

Brian Higgins, a retired police chief of Bergen County, N.J., and current adjunct professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, explained that if Oregon State Police officers are deputized as federal officers, they could charge suspects in federal court under federal statutes rather than local or state laws.

Higgins said the practice of federally deputizing state or local police officers is not uncommon. “As a matter of fact,” he said, “it’s done pretty regularly,” typically in situations where local officers are asked to serve in a capacity that is outside their normal jurisdiction — for example, working on a gang unit or other type of special task force involving federal crimes, or providing security for large-scale national events such as the Super Bowl or political conventions.

In the context of protests, Higgins said he’s also seen local officers become deputized to protect federal property. However, the concept of using federally deputized officers to pursue federal charges against people arrested for offenses related to protests “is probably a new approach” in response to “the conflict that’s going on in criminal justice right now between prosecutors and law enforcement.”

“It’s almost as if law enforcement is finding another alternative to just protect themselves,” said Higgins, explaining that “in certain parts of the country,” including Portland as well as New York City and Chicago, there is a sense of frustration among law enforcement officials who believe ongoing unrest is being enabled by progressive local prosecutors who’ve chosen to either downgrade or drop charges stemming from protests against police violence and systemic racism.

“It almost appears to me as if this lack of charging or downgrading charges in protests, particularly in charges related to assaulting police officers, may contribute to more assaults against police officers because protesters think that they just will not be held accountable,” he said.

In an email to Yahoo News, Kevin Sonoff, a spokesperson for the U.S. attorney for the district of Oregon, confirmed that “select Oregon State Police troopers have received special deputation by the U.S. Marshals Service,” authorizing them under the federal criminal code to detain and make arrests and, “when necessary, to protect and defend federal government buildings and personnel during a civil disturbance.”

“The U.S. Attorney’s Office will evaluate all arrests made by Oregon State Police troopers under this authority for federal prosecution,” said Sonoff.

Sonoff did not respond to multiple follow-up requests for confirmation of when exactly this select group of state troopers received their special deputation, nor did spokespersons for the U.S. Marshals Service. But according to Tim Fox, a public affairs officer with the Oregon State Police, “Troopers were originally deputized when we provided protection for the federal courthouse.”

State troopers were deployed to protect the Mark O. Hatfield United States Courthouse in late July, replacing federal officers who had been sent to guard federal property in Portland over the objections of Gov. Kate Brown and Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler. An agreement between Brown and Trump administration officials called for the federal officers to withdraw and be replaced by Oregon State Police.

The state police deployment lasted only until Aug. 14, which an OSP spokesperson says was the duration of the commitment. But the OSP statement also included an implicit criticism of the policy of Schmidt, the district attorney, to not prosecute certain protest-related offenses — including interfering with police, disorderly conduct, criminal trespass, escape and harassment — unless the allegations involve “deliberate’’ property damage, theft or force against another person or threats of force.

“At this time we are inclined to move those resources back to counties where prosecution of criminal conduct is still a priority,” the OSP spokesperson said in a statement confirming the withdrawal from Portland.

The district attorney’s new protest policy also required that any charges of “resisting arrest” and “assaulting a public safety officer” be subjected to “the highest level of scrutiny by the deputy district attorney reviewing the arrest,” with consideration given to “the chaos of a protesting environment, especially after tear gas or other less-lethal munitions have been deployed against community members en masse.”

Since OSP officers left in mid-August, unrest in the city has continued pretty much unabated, with increasingly violent clashes between opposing political factions leading to the fatal shooting on Saturday of Aaron J. Danielson, a Portland resident affiliated with the far-right group Patriot Prayer, which has been at the center of previous clashes with left-wing protesters. (A suspect, Michael Forest Reinoehl, was killed Thursday while federal officers attempted to arrest him near Lacey, Wash., about 120 miles away.)

Now the troopers are back. On Sunday, Gov. Brown outlined a “unified law enforcement plan” calling for assistance from local, state and federal law enforcement resources to “protect free speech and bring violence and arson to an end in Portland.” While law enforcement officials from neighboring jurisdictions quickly declined the governor’s requestto contribute additional personnel and resources to assist the Portland police, the Oregon State Police sent assistance in the form of state troopers who’d been cross-deputized by the U.S. Marshals Service.

Higgins said the decision to send federally deputized state troopers to Portland “might be a good option for law enforcement” there, adding that “in certain areas where there is this conflict between prosecutors and law enforcement, I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s done again.

“I can tell you most law enforcement executives are sitting up a little straighter and taking notice right now,” he said.

But Higgins said he does not expect this approach to “take off across the country,” and, perhaps more importantly, “I would caution that this not be the norm.”

In particular, he noted that the rules regarding use of force for federal officers are different, and typically much broader, than the parameters set for police under their respective state and local laws. Allowing officers to operate under two different authorities with drastically different use-of-force limits is “kind of a slippery slope,” Higgins warned.

“That’s a concern, and it’s why we don’t have a uniformed federal law enforcement agency throughout the country,” he said.

“It shouldn’t come to this, quite frankly,” Higgins continued. “There should be more of a consensus between prosecutors and law enforcement, and more about public safety and a lot less about politics.”

*story by Yahoo News