In 2015, a Louisiana State University freshman transferred schools weeks after he was accused of sexual assault. LSU did not disclose the allegation to his new school, even after learning of his arrest for allegedly assaulting a second woman months later.

The same year, the University of Louisiana at Lafayette placed a student arrested for sexual assault on probation, letting him stay on campus so long as he stayed out of trouble. Over his next three years there, three women reported him to the Lafayette Police Department for sex crimes, but the police never informed the school, despite an agreement that required it.

In 2018, Louisiana Tech University declined to investigate a woman’s sexual assault report because the alleged perpetrator dropped out of the school three days after she reported it. The university said nothing to the school he transferred to the next month.

In each case, the institutions failed to share relevant information with each other, leaving women on their campuses without warning and potentially at risk.

The cases also share another common thread. They all involved the same accused student: Victor Daniel Silva.

Silva, who did not respond to requests for comment for this story and hung up the phone on a reporter, has never been charged with a sex crime. He was arrested once but prosecutors did not move forward with the case. He has told police and others the allegations against him are false.

His case, however, illustrates how universities continue to struggle with the most basic response to sexual assault allegations. Over and over when women came forward about Silva, college officials and police didn’t communicate, didn’t convey critical information, and didn’t connect the dots on a pattern that might have shaped how they pursued the allegations.

This was supposed to have changed in Louisiana. Six years ago, in response to a reckoning over the handling of sexual assault cases across the state, Louisiana legislators enacted a sweeping new law designed to root out predators on college campuses.

Known as Act 172, the law required universities and local law enforcement agencies to alert each other to reports of alleged sex crimes involving students in their areas. It ordered colleges to block students from transferring schools during sex-offense investigations, and to disclose any resulting disciplinary actions to incoming schools.

Police and universities at the time already had a mandate to investigate campus sexual misconduct. The 2015 law was supposed to make that job easier by ensuring everyone had information about accused students who otherwise might have slipped through the cracks.

But one by one, the people in charge of protecting students at three of the state’s largest public universities either failed to comply with its provisions or found loopholes to avoid them, according to a USA TODAY investigation based on a review of case files, a trove of documents, emails and other public records, and interviews with current and former prosecutors, police officers, lawmakers, university officials and seven women who alleged sexual assaults.

Because officials failed to communicate with each other, they viewed nearly every allegation against Silva as an isolated incident in an otherwise clean record. They closed every case against him without a finding of fault, sometimes without investigating, with no interruption to his education.

Their failures show how the mishandling of sexual misconduct allegations extends beyond just the state’s flagship university, LSU, which has come under fire after investigative reporting by USA TODAY found school officials covered up reports of rape, domestic violence and harassment and botched investigations under Title IX, the federal law prohibiting sex discrimination in education.

“It is impressively embarrassing to our state,” said J.P. Morrell, an attorney and former state senator who sponsored Act 172. “At best, it is a complete, callous disregard for what victims are going through — and not just what they’re going through, but what the future victims will go through, as these predators find new victims.

“At worst, it’s almost malicious.”

Officials at LSU, UL Lafayette and Louisiana Tech denied wrongdoing, saying they complied with all laws and policies at the time.

Top brass at the Lafayette Police Department, including the chief, ignored at least nine emails and phone messages seeking comment. Jamie Angelle, a spokesperson for the city of Lafayette, emailed a statement saying the police agency’s agreement with UL Lafayette, which is mandatory under Act 172, did not require it to inform the school of “unsubstantiated allegations.”

The agreement, however, requires the agency to “notify UL Lafayette’s Title IX Coordinator… of any report of a sexually oriented criminal offense that may have occurred on its campus or involved a student as a victim or an accused.”

Morrell and another former lawmaker who wrote the 2015 state law – Helena Moreno, who currently serves as New Orleans’ City Council president – told USA TODAY the requirements were clear.

The schools and law enforcement, they said, simply didn’t follow them.

***

An oppressive heat baked the UL Lafayette campus the afternoon of June 22, 2015.

It was a Monday, and Carl Tapo sat in his office on the first floor of Buchanan Hall, a low-slung, red-brick structure across the street from a two-acre swamp – the nation’s only managed wetland on a college campus. Tapo, then a 62-year-old assistant dean of students, had an appointment with Silva, a recently transferred student who got into trouble.

What Tapo knew about him was this: Silva, a freshman, arrived at UL Lafayette that January after a semester at LSU. Just over two months after his transfer, following a visit to friends at his old school, LSU campus police arrested Silva on a charge of second-degree rape.

According to the police report, after a night of drinking at a popular bar near the Baton Rouge campus that March, an LSU student who’d known Silva from the previous semester let him into her dorm room. Shortly afterward, the report said, Silva used his bodyweight to hold down the woman as he raped her at least three times over the span of three hours.

LSU police got a warrant for Silva’s arrest on April 1, 2015, and booked him in the parish prison. His mugshot made the local news and the rounds on social media among students at both universities. One news article found its way to Tapo’s email inbox, sent by an LSU administrator as a courtesy.

But in the two-and-a-half months between Silva’s arrest and his meeting with Tapo, the case seemed to have fizzled.

The East Baton Rouge District Attorney’s Office had not filed charges. LSU hadn’t reached out again to Tapo with an update. No one at UL Lafayette had heard from the alleged victim, who, even as an LSU student, could have filed a Title IX complaint against Silva at his new university.

And as far as Tapo knew, Silva, who denied the allegations, had never been accused before.

Tapo went easy on Silva. He placed the 19-year-old on disciplinary probation for two years and ordered him to attend behavior management sessions at the school health center.

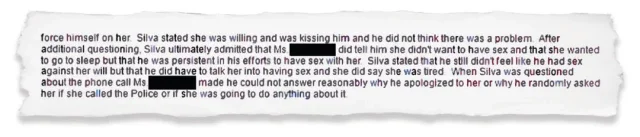

What Tapo didn’t know was this: Two months into Silva’s first semester at LSU, a different LSU student he’d met in an English class accused him of rape.

Because the incident happened in Lafayette, the woman reported it to Lafayette police. Police notified LSU a day later.

LSU, which had no full-time Title IX employees at the time, launched an investigation into the woman’s complaint. It sided with Silva, according to case records obtained by USA TODAY via public records request. He faced no discipline.

The District Attorney’s Office for the 15th Judicial District Court, which serves Lafayette Parish, also declined to file charges against Silva in the case, citing a lack of evidence, records show.

Because LSU cleared Silva of wrongdoing, administrators did not notify UL Lafayette of the allegation when Silva transferred there at the end of the semester, vice president of communications Jim Sabourin told USA TODAY. They had “no reason to” do so, Sabourin said, nor did any policy or law require it.

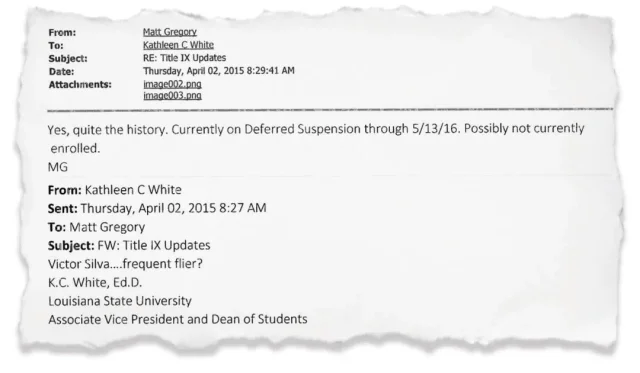

But LSU did share information about Silva’s April 2015 arrest.

According to emails obtained by USA TODAY through public records requests, upon learning of the second rape allegation, LSU officials described Silva as a “frequent flyer” whose name had appeared in the school’s conduct files the previous semester. They moved quickly to ban Silva from campus, emails show. But when they notified UL Lafayette about his arrest, they still made no mention of the prior allegation.

As a result, the report that prompted Silva’s arrest appeared to UL Lafayette as a first-time accusation.

One day after Tapo’s meeting with Silva, Louisiana’s then-Gov. Bobby Jindal signed Act 172 into law, along with three other bills designed to protect survivors.

“I’m proud to sign these crucial pieces of legislation into law that support and empower victims of sexual assault,” Jindal said in a press release at the time.

Jindal, a Republican, announced his candidacy for president the next day.

In an email to USA TODAY, UL Lafayette associate vice president of communications Jennifer Stephens said the university “took appropriate actions according to what it knew at the time and within the confines of existing state law and federal guidance.”

In addition, Stephens said, U.S. Department of Education guidance at the time specifically addressed how schools should respond to students’ sexual assault complaints when the alleged perpetrator is not affiliated with the school: “The home school should notify the student of any right to file a complaint with the alleged perpetrator’s school or local law enforcement.”

But Mayumi Dickerson, the woman who reported Silva, said in an interview with USA TODAY that LSU never informed her of her right to file a complaint against him at UL Lafayette. Had she known it was possible, she said, she would have done it.

It is USA TODAY’s policy not to publish the names of people who allege sexual assault without their permission. Dickerson and two others chose to use their full names.

The same month that UL Lafayette placed Silva on probation, LSU expelled Dickerson because her grades had plummeted.

The scholastic drop was unrelated to her sexual assault allegation, according to Sabourin, who said the university took a series of academic actions against Dickerson starting before the incident.

LSU ultimately allowed Dickerson back in, after she filed a U.S. Department of Education complaint alleging the school violated her rights under Title IX. Her complaint prompted a sex-discrimination investigation into the school by the department’s Office for Civil Rights.

But Dickerson had developed post-traumatic stress disorder and become terrified to set foot on campus, she said, in part because Silva’s friends at LSU had harassed her on campus and pressured her to drop the charges. She left LSU a year later.

Neither university’s Title IX office investigated Dickerson’s complaint.

“My college experience has been 100% altered because of him and everything that I’ve been through,” Dickerson said. “I get super nervous just walking on a college campus. I’m still working toward my undergrad degree. He got to have those experiences that he stripped me of.”

***

Tapo’s decision to place Silva on probation allowed him to continue his coursework at UL Lafayette without interruption – so long as he stayed out of trouble.

Silva attended his mandatory counseling that July, school records show. The same month, he started a research assistantship with a chemistry professor, designing processes to extract oil from the Gulf of Mexico, according to his resume. That August, he started a side job through a university program tutoring high school students.

Silva remained enrolled at UL Lafayette for the next three years, attendance records show. During that time, the school received no reports of sexual misconduct allegations against Silva, Stephens said.

As far as university officials knew, Silva had completed his probation without issue.

But unbenknowst to school officials, at least three women had reported Silva to the Lafayette Police Department for sex crimes during that time. One of them was a UL Lafayette student whom Silva had tutored through the school program.

None of the three reports was shared with the university.

Under Act 172, each Louisiana university was required to enter into a memorandum of understanding with the law enforcement agencies in their surrounding areas, outlining protocols for investigating and notifying each other about alleged sex crimes involving students.

UL Lafayette’s memorandum with LPD required the police to “(n)otify UL Lafayette’s Title IX Coordinator, to the extent we are able with respect to any confidentiality requirements, of any report of a sexually oriented criminal offense that may have occurred on its campus or involved a student as a victim or an accused,” according to a copy obtained via a public records request.

Yet for each of the three reports against Silva, LPD officers ignored the requirement.

The first came in November 2016, while Silva was still on probation. According to the police report, a local community college student who had met Silva on a dating app a year earlier said he was now trying to blackmail her.

The woman, who spoke to USA TODAY, told police she and Silva had consensual sex about a year earlier. Then, out of the blue, he sent her a video of the encounter that he had apparently had recorded without her knowledge. When she told him to delete it, he said he would – in exchange for nude photographs.

The woman immediately called LPD and talked to Officer Jonathan Richard, the report shows. She told Richard she would forego criminal charges if Silva would delete the video.

Richard then called Silva, who agreed on the phone to delete it, according to the report. Richard closed the case.

Although the memorandum required LPD to notify UL Lafayette about the incident, LPD did not sign the agreement until two months after the report, in January 2017 – more than a year after Act 172 took effect.

Even after signing it, the police department failed to share at least two more accusations against Silva with the university.

Both of those cases, records show, were assigned to Detective James Gayle.

Gayle first met Silva on June 8, 2018. They sat across from each other in a small interview room at the police station to discuss a sexual assault report made against him that April by a fellow UL Lafayette student. Seated next to Silva was his criminal defense attorney, Josh Guillory, who was elected mayor-president of Lafayette the following year – a position he holds today.

According to the April 2018 police report against Silva, the student met him in 2016 through the tutoring program he worked for at UL Lafayette. The first time they hung out, she told police, he groped her and vaginally penetrated her against her will. She decided to report it two years later, when she learned of other allegations against him that had been posted on social media.

Gayle read Silva his Miranda rights and asked him what happened that day. Silva denied the allegation and said the encounter was consensual.

After 20 minutes, Gayle ended the interview. He told Silva he’d send the case to the 15th Judicial District Attorney’s office for a charging decision.

The district attorney’s office also was a party to the memorandum. It, too, was required to notify UL Lafayette of “any report” of a sex offense involving a student as a victim or suspect, the agreement shows.

But neither the district attorney’s office nor LPD did so.

Less than two months later, a second UL Lafayette student reported Silva to LPD. Andie Richard-Bonano said Silva sexually assaulted her in 2010, when they were 14, on the morning of their freshman orientation at St. Thomas More Catholic High School.

Richard-Bonano, who spoke to USA TODAY, had disclosed her alleged assault by Silva on social media for the first time two years earlier. She did so after seeing another woman, Carolina Chauffe, post on Facebook that Silva had sexually assaulted her the same year, when she was 12.

“I was ready to have it on record that this man is a monster and has hurt people before and will continue to do it,” Richard-Bonano told USA TODAY.

Richard-Bonano said she remembered Gayle telling her that her complaint probably would not lead to charges, but that it may be useful to establish a pattern if other victims came forward.

Richard-Bonano was at least the fifth person to report Silva to police for a sex crime by that time, and the fourth to report him to LPD.

It’s unclear what Gayle did with her report. LPD refused to provide it in response to public records requests by both USA TODAY and Richard-Bonano, citing that she and Silva were minors at the time of the alleged crime. It said it would provide the report if she signed a non-disclosure agreement promising not to share its contents with anyone. She declined.

USA TODAY made at least nine attempts to reach LPD Chief Thomas Glover, Gayle and four sergeants, including public information officer Wayne Griffin, for comment. None responded.

“It would be improper, if not unlawful, to report unsubstantiated allegations, which by definition do not fall within the scope of the MOU,” said Angelle, a spokesperson for the city of Lafayette, in an emailed statement to USA TODAY.

Angelle also sent a statement on behalf of Guillory, the current mayor who represented Silva in not only the April 2018 case, but also in the October 2014 case from his first semester at LSU.

“At the request of his parents, I attended two interviews with Mr. Silva,” Guillory’s statement said. “He was not charged in either instance, and did not further require legal representation.”

Alan Haney, an assistant district attorney for the 15th Judicial District, said he believed his office complied with Act 172 but did not dispute that it did not notify UL Lafayette of the allegations.

The memorandum of understanding is unequivocal, said Moreno, the former state representative who co-authored Act 172 and reviewed the agreement. It states both LPD and the district attorney’s office must share “any report” of a sexually oriented criminal offense with UL Lafayette’s Title IX coordinator.

The police agency and the district attorney’s office, Moreno said, clearly violated it.

“This MOU process was specifically put together for this reason, so that the university would know if they had some type of serious situation on their hands,” Moreno said. “I mean, my God, you have a potential serial rapist on your campus? The campus should be alerted.”

***

In September 2018, just weeks after the latest police report, Silva transferred to Louisiana Tech University in Ruston, a rural town of 22,000 in the northern part of the state.

He arrived with a clean record.

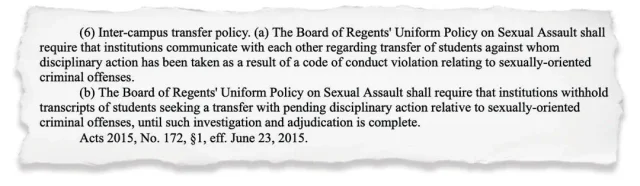

Although the law requires universities to “communicate with each other regarding transfer of students against whom disciplinary action has been taken as a result of a code of conduct violation relating to sexually-oriented criminal offenses,” UL Lafayette did not notify Tech about Silva’s probation from his arrest for rape.

That’s because of a technicality involving the timing of Silva’s discipline.

Act 172 specifically directed Louisiana’s Board of Regents, which oversees the state’s public universities, to adopt a policy mandating such communication. It did so in August 2015 – two months after UL Lafayette placed Silva on probation.

Because the board policy had not yet taken effect at the time of the discipline, Stephens told USA TODAY, the university did not flag Silva’s conduct record and was not required to notify Tech when he transferred there three years later.

Additionally, Stephens said, because Silva completed the probation prior to his transfer, there was no disciplinary hold on his transcript.

Stephens insisted that UL Lafayette violated no laws or policies.

“That said, the University recognizes opportunities to strengthen processes and procedures related to student transfers and the reporting of student disciplinary issues,” she said in an email, adding that school officials are currently helping the legislature develop new laws on these issues. “We also strongly reiterate that the University takes all accusations of sexual assault seriously and recognizes the accusations made against Mr. Silva were serious.”

Silva’s time at Tech lasted just three months.

In December of that year, a fellow Tech student filed a report with the school’s Title IX office and campus police department alleging that Silva had sexually assaulted her in his apartment three months earlier – less than two weeks after he enrolled – while she was unconscious from drinking alcohol, police reports show.

Because the incident happened off-campus, Tech police referred it to the Ruston Police Department, which interviewed the woman the same day, records show. RPD later referred the case to the Third Judicial District Attorney’s Office, which serves Ruston. It declined to charge Silva.

The week after the woman reported the incident, Tech associate vice president for student advancement Dickie Crawford called her into a meeting, where she told her the university would not be investigating her case, the woman told USA TODAY.

Silva had withdrawn from the university three days after she filed the report. As a result, Crawford told the woman, Tech no longer had jurisdiction to punish him.

Silva transferred back to UL Lafayette the next month.

Act 172 required universities to prevent students accused of sex offenses from transferring schools to avoid an investigation or punishment. Specifically, the policy the board adopted to comply with the law said, “If a student accused of a sexually-oriented criminal offense seeks to transfer to another institution during an investigation, the institution shall withhold the student’s transcript until such investigation or adjudication is complete and a final decision has been made.”

Yet Tech did not withhold Silva’s transcript or notify UL Lafayette of the allegation.

According to Tech attorney Justin Kavalir, Silva withdrew from the university so quickly after the woman’s report that it didn’t have time to begin an investigation. As a result, because there was no pending disciplinary case against him, the policy did not apply, Kavalir said.

Morell and Moreno, the two former state lawmakers who co-authored Act 172, were incensed by Tech’s failure to pursue an investigation into Silva.

“That’s literally what that section of the law was supposed to address, that you don’t get to skip town and not have an investigation,” Morrell said. “The situation you’re describing is literally finding a loophole in the law to avoid protecting sexual assault victims and exploiting it. That’s really offensive. It’s offensive, and it’s just – it makes me nauseous.”

The requirements of Act 172 are clear, Moreno said. What is lacking in the law, she said, is oversight for the universities that continually find excuses not to follow it.

“It just appears that everyone does what they want to do anyway, and laws are ignored, and backs are turned, and tracks are covered,” Moreno said. “Unfortunately, it’s the victims who are left without any real help.

“And unfortunately, if this isn’t really corrected, and this isn’t really prioritized, nothing’s going to change, and there are going to be more victims.”

***

Silva strode across the artificial turf of Cajun Field, the UL Lafayette football stadium, on the evening of Aug. 7, 2020, in a vermilion cap and gown.

With the dean of the College of Engineering standing behind him, he smiled for a photo, holding his bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering against his chest.

As he walked off the field at the end of the ceremony, Silva looked to the bleachers and waved to the crowd.

Over his six years in college, at least six women at three universities had reported him for alleged sexual offenses to four police agencies across three parishes. He had been banned from LSU’s campus, arrested but not prosecuted, and placed on probation by UL Lafayette. But Silva never missed a semester of classes.

Other than his 2015 arrest, UL Lafayette was unaware of any other allegations against him, Stephens told USA TODAY. The university received no complaints against Silva in his first three years as a student, nor his last year and a half.

But his final days at UL Lafayette were not without incident.

In the spring of 2020, Silva began dating Nicole Pellegrin, a fellow chemical engineering student who shared classes with him and spoke to USA TODAY. She went into the relationship wary, she said, after reading a news article about his 2015 arrest and seeing other allegations on social media. But he told her he’d been falsely accused and never convicted, and she gave him the benefit of the doubt.

Two days before the graduation ceremony that August, Pellegrin invited her longtime best friend to have dinner with her and Silva. The friend, an LSU student who spoke to USA TODAY, said she had been unaware of the allegations against him.

After a night of drinking, the friend stayed the night in Pellegrin’s guest bedroom. At around 5 a.m., she said, she woke up to find Silva curled up in bed with her. His body was pressed up against hers, she said, and he was erect. His arms were wrapped around her, and his hands were under her shirt, fondling her breasts.

It took a few seconds to process what was happening, the friend said, before she pushed Silva off. He acted like he didn’t know where he was, she said — like he’d accidentally fallen asleep in the wrong bed.

The friend told Pellegrin what happened later that morning, she said, but Pellegrin did not believe it at first. Because he sometimes slept in the guest room, Pellegrin took Silva’s word that it was a drunken mistake.

This strained the women’s eight-year friendship, they told USA TODAY. Losing that is “sometimes harder than what actually happened to me,” the friend said.

Pellegrin said she now believes the women who’ve accused Silva and regrets letting him manipulate her.

“I did really love him a lot,” Pellegrin said. “But the person I loved is not the person he actually is. It never was. He’s great at pretending, and he needs to be held accountable. I should have stood by my friend.”

After Googling Silva and learning about other allegations against him, the friend strongly considered pursuing a criminal case, she said.

Her father hired a private investigator to look into Silva’s past, documents she shared with USA TODAY show. She consulted with her stepmom, who’s a lawyer, and a New Orleans prosecutor with whom her family was close. They warned her a trial would likely be retraumatizing, she said, and the chances of a conviction slim.

The friend ultimately decided not to report Silva. She didn’t see the point.

*story by USA Today