Anthony Dart clicked the slide of his Glock 17 into place. His target, a cardboard stencil of a human body, dangled from an easel across the room.

All was still in Dart’s East Oakland studio loft, where a bag of oranges sat on the granite countertop and Donny Hathaway crooned from the stereo. Guns lay on the coffee table, beside a protractor and a jar of beet juice. Glocks, a Smith & Wesson M&P 15 rifle and a Ruger Pistol Caliber Carbine, partially disassembled so he could clean out the barrel.

The 43-year-old firearm instructor set the pistol down. “It helps with immediate danger,” he said of being armed.

In some senses, Dart, who is Black, serves as an evangelist for the idea that guns can provide freedom and empowerment. Yet he’s promoting his message in a diverse part of the city with a complex and anguished relationship with guns.

Firearm sales soared across California last year, even as the number of gun dealerships continued to decline, according to the state Department of Justice. The chasm between gun enthusiasts and gun control advocates appears to be widening, and it’s particularly stark in places like Alameda County, where gun crimes — and requests to carry the instruments that cause them — are escalating.

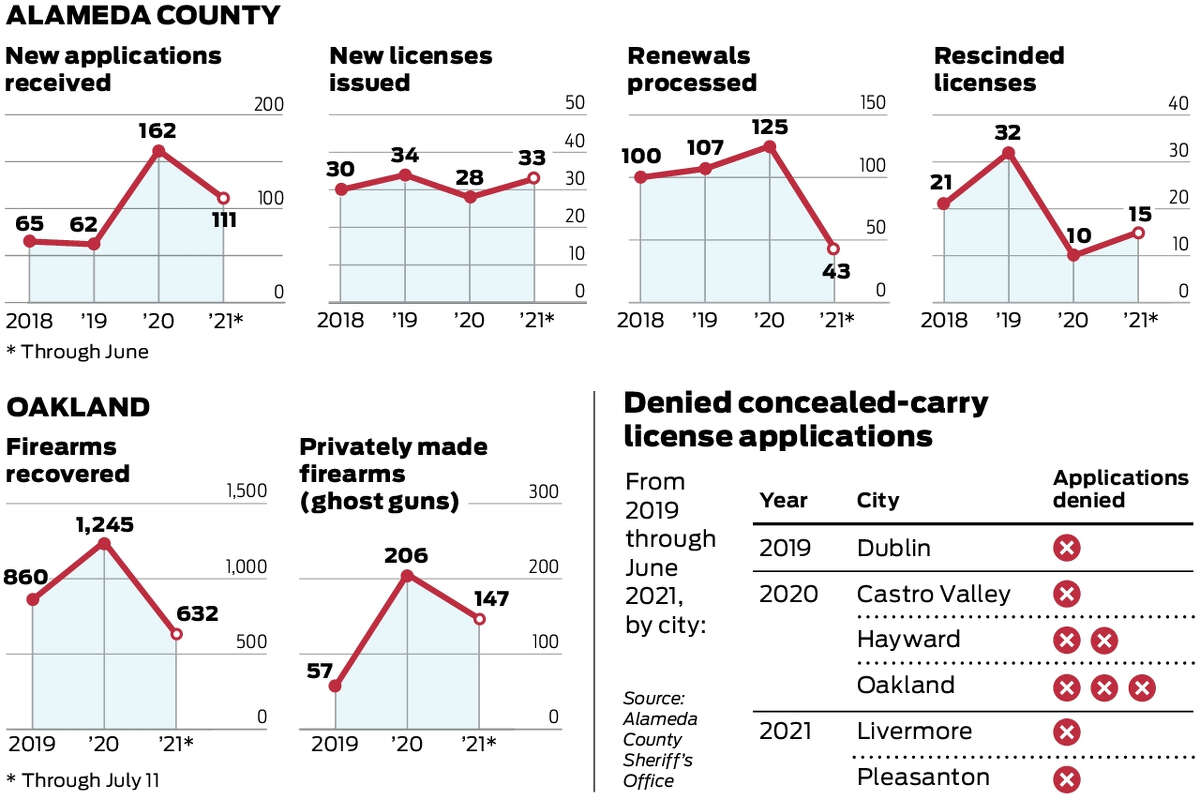

Applications to carry concealed handguns more than doubled in Alameda County last year, from 62 in 2019 to 162 in 2020, according to records obtained by The Chronicle. By June, officials had already received 111 new applications, signaling a new peak could be coming this year.

Most requests aren’t granted, the data shows. The Alameda County Sheriff’s Office approved only 95 of the 335 applications it received from 2019 through the first half of 2021 and denied only nine, leaving nearly 70% of new applications unresolved. A Sheriff’s Office public records employee said the vast majority of the pending requests are “shunned right away” for lacking good cause, which is a basic requirement.

As the number of new applications spiked during the pandemic, the approval rate actually dropped, from 55% in 2019 to 17% in 2020 and 30% so far this year.

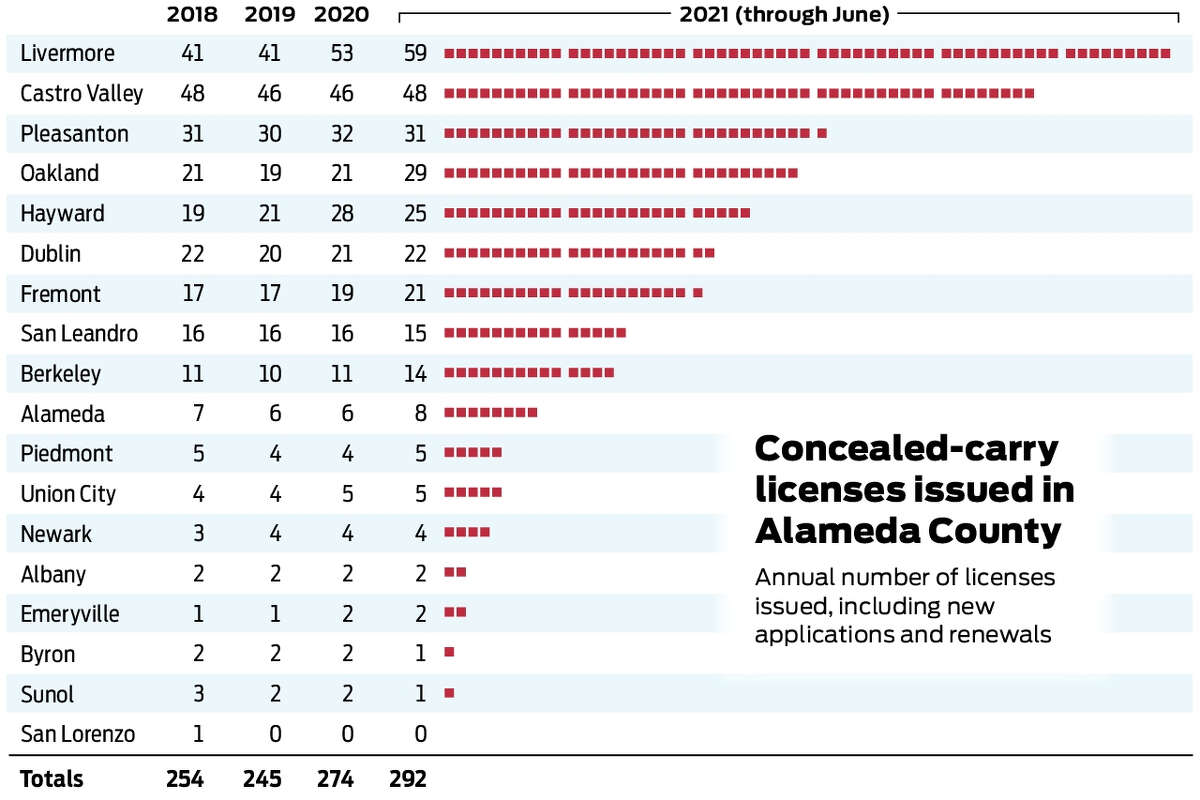

Suburbs have the highest number of concealed-carry permits, with 59 active licenses in Livermore and 48 in Castro Valley. In comparison, Oakland has 29 active licenses, though the area still appears to be saturated with firearms.

Oakland police have recovered 727 firearms and recorded 78 homicides through Aug. 10 this year, mostly clustered in the flatlands of East Oakland. Many of the guns seized or found by police, or turned in by residents, have no serial number and cannot be traced, said Capt. Roland Holmgren, commander of the Police Department’s Violent Crime Operations Center.

A large body of academic research has linked gun ownership to higher rates of injury and death. Among the findings: In California, male gun owners take their own lives at nine times the rate of men who don’t own guns, and women are 35 times more likely to kill themselves if they own a handgun, according to a Stanford University study published last year in the New England Journal of Medicine.

A 2014 review published in the Annals of Internal Medicine concluded that the presence of a gun in the home doubled the risk for homicide and triples the risk for suicide.

Despite the risk factors, guns carry a different weight in East Oakland, where historic disinvestment has exacerbated everything from the foreclosure crisis to the coronavirus pandemic in communities that were once predominantly Black and are now majority Latino.

“Let’s be honest, in my neighborhood, pretty much everyone has guns,” Keisha Henderson said of the flatlands area near 55th Avenue, which is about half a mile from Dart’s studio.

Henderson, who serves on the Neighborhood Crime Prevention Council, cited several reasons that her neighbors are more inclined to arm themselves. They range from slower police responses as a smaller force grapples with a spike in killings to the specter of racially motivated attacks. Fears flared up, she said, after the killing of Black jogger Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia, the Jan. 6 raid on the U.S. Capitol and a recent string of viral videos purporting to show hate crimes.

Dart said he has a permit to carry a concealed firearm, but only does so “about 5% of the time.”

“Just when I feel it in my gut,” he said.

To Dart, legal gun ownership is as much a civil rights issue as anything else. He said that Black people face more obstacles trying to exercise their Second Amendment rights.

“I always hear in the Black community that it’s hard for Black and brown (people) to get firearms,” he said.

Black people aren’t just excluded from being customers in the firearm industry, Dart contended. California only has one Black-owned gun store, Redstone Firearms in Burbank.

To open a gun store in California, aspiring business owners must obtain a federal license, a seller’s permit from the State Board of Equalization, a certificate from the state Department of Justice and placement in the department’s Centralized List of Firearms Dealers, apart from business permits required by the city or county.

In Oakland, sellers of guns and ammunition must pay $24 for every $1,000 of merchandise sold, under a measure approved by voters in 1998. Additionally, all dealers must apply for a permit from the city’s police chief. Oakland’s last gun store closed in 2000.

Dart said he tried for three years to open his own store in the city, but couldn’t find a landlord willing to rent him a storefront, let alone the bank capital to start a business.

*story by The San Francisco Chronicle

“I tell them I want to open a gun store. They’re like, ‘Oh no, we don’t want this here,’” he said, referring to what he saw as resistance from all sides.

A decline in gun dealerships hasn’t prevented more guns from flowing into California, legally and illegally.

The year 2020 set a record for the most handguns sold in a single year in California, the state Justice Department says. The previous year, law enforcement agencies in the state recovered 41,884 firearms suspected of being used in crimes, according to the most recent data from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, or ATF. Sixty percent of those guns originated from outside California.

Oakland and San Francisco ranked seventh and eighth out of the top California cities where crime guns were recovered in 2019, with 891 and 802, respectively.

Regina Jackson, president of the East Oakland Youth Development Center and chair of the city’s Police Commission, said she empathizes with people who want to defend their homes and their families. But she doesn’t view firearms as the mechanism for a safer community.

“I don’t think more guns is the answer,” she said. “I want to model what it is that I want to see for my city. And if I want not to see guns everywhere, then I actually have to believe in different ways of ‘arming ourselves’ — with information, education, self-defense.”

But with homicides approaching a record not seen in Oakland in almost a decade, would that view prevail over Dart’s prescription that firearms represent part of the solution?

On the floor of Dart’s studio, feet away from a milk crate of vinyl records, is a statue he purchased while backpacking in Vietnam. It shows a warrior holding a severed head. Dart said it illustrates one of his credos — one that could apply to firearm safety.

“Either you fight and take off the other person’s head,” he said, “or you’re the one whose head is taken off.”

Though he sticks to that philosophy, Dart said he has never used a gun to protect himself, or others, in real life.

He picked up his first firearm — a derringer — as a child in Vicksburg, Miss. Dart grew up shooting for sport, a hobby he kept after moving to Oakland in 1988. Later, he came to see guns as a source of protection in a city beset by violence.

Dart estimates he’s trained more than 400 people, including many novices. He’s advertised classes for Black women who want to learn how to assemble, secure and properly shoot a pistol or rifle; others focused on defending against home invasions. He timed one class to precede Juneteenth, the day a firefight at Lake Merritt left one man dead and injured seven others.

On June 21, Dart announced that his company, Akoben Firearms Safety Training, would shut its doors. Too many people were signing up for classes and flaking, he said. In a later interview, he characterized the closure as more of a pivot: He would still offer group lessons to people who paid in advance.

The day his shop closed, on June 30, he posted a video on his Facebook page, in which Black Second Amendment advocate Rhonda Mary described gun control laws as racist “control and subjugation.”

“LISTEN!!!!!” Dart wrote in all caps.

Four days later, multiple shootings marred Fourth of July festivities in Oakland. Another person lay dead.