Vice President Kamala Harris departed Wednesday for a weeklong trip to the Indo-Pacific region, the latest move by the White House to burnish her image as the logical successor to President Biden if he won’t or can’t run in 2024.

After a rocky start in office that included frequent staff turnover and her struggling in television interviews, Ms. Harris may have found her footing in recent months.

Indeed, Washington politicos see a concerted effort by administration officials to get Ms. Harris out in front, both domestically and on the world stage.

“They are trying to send a message to other potential [2024 Democratic] candidates that they need to cool their heels because Harris is very much in the on-deck circle,” said Patrick Basham, director of the Washington-based Democracy Institute.

Ms. Harris became the administration’s point person on abortion, an issue that helped Democrats avoid a drubbing in last week’s midterms. She crisscrossed the nation stumping for Democrats, rallying the base to fight for abortion access.

In September, Ms. Harris was dispatched to Japan where she successfully walked a diplomatic tightrope expressing the administration’s support for Taiwan while not inflaming tensions with China. It’s an issue that has tripped up her boss, Mr. Biden, multiple times.

Ms. Harris won’t announce that she’ll be running for president while she and the world wait for Mr. Biden to decide if he’ll seek reelection. But she’s widely seen as among the top contenders for the Democratic primary if Mr. Biden decides to step aside.

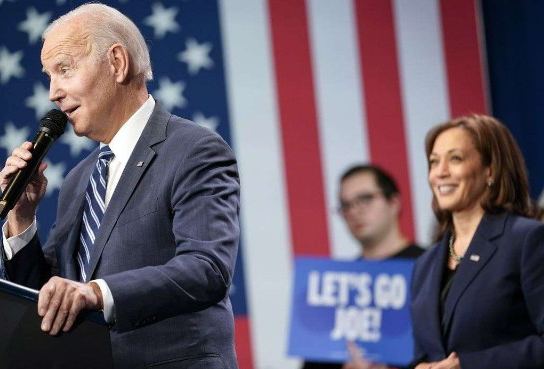

Mr. Biden says he intends to run for reelection in 2024, but won’t decide until early next year. His future remains cloudy amid low approval ratings, a birthday this month when he’ll turn 80 years old and some within his party suggesting he hang it up after one term.

When asked about her presidential aspirations during an interview on NBC News, Ms. Harris brushed off talk of running in 2024, saying she committed to winning another term for Mr. Biden.

“And if he does [run], I will be running with him proudly,” she said.

Joel K. Goldstein, a vice presidential historian at the Saint Louis University School of Law, said there is no playbook for preparing a vice president to succeed a president during an administration’s first term. Most vice presidents’ political future hinges upon the successful reelection of their boss, he said.

However, Mr. Biden’s advanced age has complicated the situation.

“For Harris, it creates an uncertainty as to whether her first term as vice president is also her second term,” Mr. Goldstein said. “It has a way of compressing things.”

Now, Ms. Harris heads to the Indo-Pacific in pursuit of bolstering her foreign policy bona fides as the Biden administration struggles with low approval ratings at home.

She will attend the Asia-Economic Cooperation summit, hold bilateral meetings with Thailand’s prime minister and the Philippines president as well as meet with other leaders, and local activists while advocating for economic stability in the region to blunt Chinese expansion.

The trip will again require Ms. Harris to walk a high-wire act when she visits Palawan, an island in the South China Sea. Beijing has claimed control over the territories, but a 2016 international arbitration ruling concluded China has no basis to exert control over Palawan, a major victory for the Philippines.

It’s the type of hands-on foreign policy experience few candidates poses in their first campaign for the White House.

During her Indo-Pacific trip, Ms. Harris will “reiterate the importance of international law,” a senior White House official said.

That could inflame already strained relations with Beijing which will look at it as unwavering support for the island’s independence. The visit will come a week after Mr. Biden sought to improve relations with Beijing through a meeting with Chinese Leader Xi Jinping.

The administration official would not say if Ms. Harris will meet with Mr. Xi, who is also attending APEC.

“If they want to make Harris look like a statesman and boost her commander-in-chief profile, the more they will give her the foreign stuff,” said the Democracy Institute’s Mr. Basham. “It’s very hard to compete with a vice president who is acting presidential.”

While the vice presidency may give Ms. Harris a leg up on her competitors, her detractors point to her consistently low approval ratings.

“The administration keeps trying to make Kamala Harris the presidential front-runner, but she’s very unlikeable,” said Jimmy Keady, a Republican strategist. “Her numbers are lower than Biden’s and she completely failed as a border czar.”

Public opinion of Ms. Harris remains low, even as Democrats performed better than expected in the midterms. The political statistics website FiveThirtyEight found that 53.2% of Americans disapprove of Ms. Harris, while only 40.1% approve.

Ms. Harris’ own presidential campaign in 2020 crashed and burned before the Iowa caucuses.

Her tumultuous role overseeing the administration’s policies has generated fierce criticism from Republicans and others. Ms. Harris took flak last year after declaring the U.S. borders are secure and for not visiting the area.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbot, a Republican, sent a bus full of migrants to Ms. Harris’ residence in September, vowing to continue to send migrants to sanctuary cities until Mr. Biden and Ms. Harris “do their jobs to secure the border.”

Still, Mr. Biden picked Ms. Harris as a running for a reason. She brought to the ticket her credentials as a former senator and attorney general for California.

She also made history as the first woman, Black woman and American of South Asian descent to serve as vice president. The prospect of her bringing those same firsts to the presidency could frighten off some challenges, said Cathy Allen, a Democratic strategist.

“She is more than your usual talent,” Ms. Allen said. “She is the poster child for the success of the nation if we have more people running the place that look and act like the rest of us.”

* Article from: The Washington Times