In late October, after four transit murders in a month, Gov. Kathy Hochul “surged” cops on the subway, allegedly sending 1,200 more officers into the trains daily. It worked — in getting the governor elected two weeks later. But a temporary police “surge” can’t stop the killings, as yet another subway murder — the year’s 10th — shows.

Early Thursday, just after midnight, cops found the body of an unidentified homeless man, fatally stabbed, at the West Fourth Street station in the Village and declared the death a homicide.

Police have released scant details, but we know enough to know it’s disturbing.

First, homeless men have been disproportionately vulnerable to random crime since New York gave up on maintaining basic order.

There were the four homeless men bludgeoned to death on Chinatown streets in an October 2019 rampage. There were the two homeless people, a man and a woman, stabbed to death on the subway in February 2021 and a third homeless man killed on a train that November, all by strangers.

And most recently, in March, a homeless man was killed in a random lower Manhattan street shooting.

So another homeless individual mysteriously dead of stab wounds in a Manhattan subway station is jarring.

It’s also jarring to have any more subway killings. This latest victim brings the 2022 total to 10 — a 43% increase over the total 2021 figure of seven.

That would be bad enough, but killings in 2021 and 2020 (also with seven deaths) were high. Between 1997 and 2019, New York had one or two killings on the subway every year.

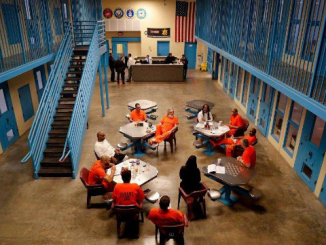

Police at the scene of where a homeless man was stabbed to death at the West 4th Street subway station on December 8, 2022.

Seth Gottfried

The crime truthers are always cracking that New York City is safer than it was in 1990. But to find a double-digit annual murder level on the subway, you do have to go back to the early-to-mid-1990s.

Third, subway murders are still regularly occurring despite the working thesis of some “transit advocates”: that as riders returned after COVID, violent crime would naturally fall, as more people would deter criminals. With subway ridership regularly at more than 60% of pre-COVID normal, far higher than in 2020 or 2021, that’s not happening.

Finally, this latest death got almost no public attention.

That’s not an accident. Since Hochul’s narrow victory, Democrats and their far-left supporters are doing everythingthey can to normalize higher crime, particularly violent subway crime.

The fatal stabbing in Manhattan was the 10th subway murder of the year.

Seth Gottfried

Through various rationalizations — 10 people is not that many victims in a city of millions, cars are more dangerous, my subway ride was great — you are supposed to gradually accept 10 subway murders a year as normal.

If we have 10 subway murders next year, Democratic pols will say that’s fine: flat over 2022 numbers. See how that works?

If they can win election now with a good percentage of the electorate still in a state of shock over the decline in public safety in New York over the past three years, they figure, they can certainly win re-election later, when we’ve all grown accustomed to it or when the people who don’t like it have left.

Yes, transit felonies are down 26% over the past month, since the policing surge began — but even before this latest killing, it was too early to declare victory. The police haven’t provided a breakdown of which crimes are down.

The story of the subways for the past three years has been that nonviolent larcenies have fallen while random violent crimes — the kind people actually worry about — have surged. There’s no evidence that has changed in a month.

And the policing surge, dependent on cops working overtime, was never sustainable.

Unless New Yorkers keep up their outrage, they can expect the extra police to melt away as close-election memories fade.

Indeed, when I walked through the same West Fourth Street subway station last Tuesday evening, two unhinged men were yelling at each other as they propped open an exit gate for people to stream through without paying. They seemed to be fighting over which one of them would get the “donation” for providing this service.

There was no police presence at what has become a troubled station peopled by vagrants who often prey on each other.

Little more than 24 hours later, someone was dead, and post-election New York got a little more accustomed to what three years ago would have seemed an unfathomable toll.

Nicole Gelinas is a contributing editor to the Manhattan Institute’s City Journal.

* Article from: The New York Post