History is a bit like Otto von Bismarck’s famous line about sausages and laws, which, he said, no one should watch being made. Think of all the people you’ve seen in pictures and statues or on coins and currency. Consider figures captured in busts and memorialized in books. Visualize military conquerors and nation builders.

Who among them meets current standards of purity? Think Roman emperors, British kings, Turkish sultans, Russian tsars, medieval popes, Mongolian khans, multinational generals, German kaisers, and more. Good luck. Maybe an abstemious monk or long-lost Vestal Virgin would pass the test. But not even many of them.

The problem is not just being born before the present rules were promulgated by Wokedom’s high priests. How many modern men and women can meet those standards and survive scrutiny? Even the sainted Barack Obama opposed gay marriage while serving as president. So did a majority of voters in California just 14 years ago, including many African Americans. Joe Biden opposed busing long ago, a heresy for which he was criticized by then-candidate Kamala Harris. Should they all be driven from the public square and confined in cultural purgatory, never to be heard or seen again?

The purge of American history continues.

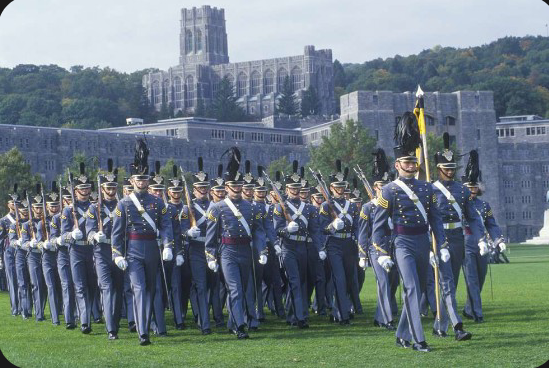

West Point says it intends to remove a bust and portrait of Lee, rename streets and buildings named after him, and even replace a quote from him in a plaza. Apparently, evidence of the academy’s most celebrated graduate — second in his class with no demerits, appointed superintendent later in his career, and celebrated Civil War general who met many of his subordinates and adversaries while running the famed institution — will disappear. It will be as if he never existed.

The killing of George Floyd and cascade of protests triggered a political tsunami against past remembrances. It was not just statues of Confederate generals that were taken down. The North’s commander, Ulysses S. Grant, suffered the same humiliating fate. A statue and mural of President George Washington were targeted. President Thomas Jefferson and “Star Spangled Banner” composer Francis Scott Key also were deemed to be beyond the pale. Congressional legislation to rename Washington, D.C., seems only a matter of time.

(Not that I am against every proposal to take down statues. Consider one of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, more responsible than anyone else for creation of the Soviet Union, which killed and imprisoned tens of millions of people. Woodrow Wilson, who though a celebrated liberal happened to be a virulent racist, also is on my hate list.)

Despite the fevered and hurried campaign — often punctuated with violence — there was a sound basis for reconsidering celebration of public figures from a different time and viewed differently by current residents. It was painful for many to tear down Monument Avenue in Richmond — the last publicly owned statue of a Confederate in the city was recently removed — but the state capital had changed dramatically over the last 130 years since the Lee monument was erected. Although I wish the statues had been left alone, with an explanation placing the men in broader context, city residents had a right to decide whom to commemorate and how.

My view is similar for names of public buildings and roads, symbols on state flags, military bases, and more. Such commemorations, often really celebrations, should reflect a broad consensus. They did for the white majority for many years, but not for growing African-American and other minority populations.

Indeed, Lee likely would agree to the removal of Civil War monuments. He became the symbol of “Lost Cause” mythology only through the efforts of others after his death. Having rejected proposals that his soldiers disperse to act as guerillas instead of surrendering, afterwards he used his immense authority to promote reconciliation. He focused on education, serving as president of the small, nearly bankrupt Washington College in Lexington, Virginia. He wrote no memoirs and even opposed celebrating Confederate battlefield heroics. Asked to join a group of former blue and gray officers to plan monuments for the Gettysburg battlefield, Lee refused: “I think it wiser, moreover, not to keep open the sores of war but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife, to commit to oblivion the feelings engendered.”

Very different, however, should be the issue of names and such where the historical connections are thin and distant. For instance, the noted birder and painter John James Audubon, after whom the Audubon Society is named, was a slaveholder. There are demands that the organization change its name. So, too, some bird names that honor Confederate soldiers. The society’s Elizabeth Gray observed: “Although we have begun to address this part of our history, we have a lot more to unpack.” Attempting to eradicate everything everywhere with the slightest connection to something now out of favor — there was a lot of injustice in America and the world unconnected to slavery — is a mindless and wasteful exercise.

Moreover, history in which Confederates, in this case Lee, played an essential role should be preserved and explained. For instance, Arlington National Cemetery was placed on land inherited by Lee’s wife from her father, the adopted son of George Washington. (Burying the dead there was a war measure and personal attack on Lee by a Union general, Montgomery Meigs.)

As a child Lee lived in the city of Arlington; his boyhood home should be recognized for its significance. (When the house was placed on the market in 2021, the listing did not mention Lee, a bizarre bow to political correctness.) Washington and Lee University rejected a campaign to remove Lee from its name. (The school likely would not have survived had he not accepted its presidency.)

Then there is West Point. Lee’s role as superintendent was both admirable and historic. His reputation as the “Marble Man” in part reflected his perfect zero in demerits. He helped educate many future military leaders in the Civil War. He also served his country with great distinction during the Mexican-American War. And he was the finest general of the Civil War, certainly its best tactician, with little opportunity to play a larger strategic role given his overriding duty to protect Richmond from capture.

Were his racial views retrograde by today’s standard? Of course, but then, most Northerners also were racists. Some northern states would not allow blacks to vote; some would not even allow free blacks to reside within them. Abraham Lincoln was long a proponent of sending freed slaves to Africa, and the Republican Party supported confining slavery to the South, not eradicating it.

Lee opposed secession but, like so many other southerners, felt his greatest loyalty was to his state. His desire was not to make war on the North but to defend Virginia if it were attacked — as it was. In rejecting the offer of command of the northern army, he wrote Gen. Winfield Scott: “Save in the defense of my native State, I never desire again to draw my sword.”

Lee made the very sensible argument that political relations should be voluntary: “I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than a dissolution of the Union.… Still, a Union that can only be maintained by swords and bayonets, and in which strife and civil war are to take the place of brotherly love and kindness, has no charm for me.” The New York Tribune’s Horace Greeley expressed similar sentiments, which were shared by many Americans.

The horrendous cost of the war retrospectively added to their number. After the terrible 1864 Overland Campaign, during which Union casualties almost equaled the total number of Lee’s army, Sen. Henry Wilson of Massachusetts allowed: “If that scene could have been presented to me before the war, anxious as I was for the preservation of the Union, I should have said: ‘The cost is too great; erring sisters, go in peace.’” Alas, the dead could not be resurrected, at least on this side of the Second Coming.

There is much in Lee’s life to study and admire beyond his wartime service: Dealing with the legacy of his father, “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, a Revolutionary War hero who squandered his family’s assets and fled overseas to avoid his creditors. Spending years serving in the spartan U.S. Army with minimal opportunities for promotion. Managing the estate of his improvident father-in-law, George Washington Parke Custis (which was Lee’s chief connection to slavery, since he was an army officer, not a plantation owner). He rejected the common claim that slavery was a positive good and urged the Confederate government to arm slaves and emancipate those who served in the Confederate military.

He had to deal with the painful challenge of dual loyalties, something which most Americans today cannot imagine. As for the charge that he was a traitor, he, like other Confederates, sought to leave, not control the union. And every combatant in the Revolutionary War, including George Washington, who wore a British uniform and fought for King George, also was a traitor. Only their treason was ignored because they ended up on the winning side. Had Britain won, Washington might have been not only hung but also drawn and quartered, a particularly painful punishment.

Although the sentiment must be shocking to some, even a Confederate officer might warrant respect and admiration, despite having fought for a slave republic. Life and history are complex. Better that we seek to understand the past, learning from rather than repeating it.

* Article from: The American Spectator