The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in 2017 began investigating Townstone Financial, a small mortgage company in Chicago, over possible violations of civil rights law.

The bureau bars lenders from making statements that “discourage” minorities from applying for loans. Townstone may have violated that regulation, the agency said, when its employees discussed crime in Chicago on a company-hosted radio show about the mortgage market, which also advertised Townstone’s services.

The offending statements, plucked from five episodes recorded over a three-year period, included a reference to the South Side of Chicago as a “war zone,” as well as a recommendation that home sellers “take down the Confederate flag.” Merely mentioning the flag, the agency argued, could scare off black applicants.

Facing a possible lawsuit and potentially stiff penalties, Townstone in 2019 retained a consumer testing firm, Kleimann Communication Group, to see if the remarks did in fact alienate African Americans.

The results were reassuring: Not a single black Chicagoan interviewed by the firm found the radio segments offensive, according to a copy of the firm’s report obtained by the Washington Free Beacon. Some even said they were more inclined to use Townstone for mortgages after hearing its employees’ banter, which they found funny and relatable.

But in July 2020—two months after the death of George Floyd—the bureau sued Townstone anyway.

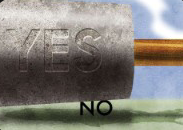

What followed was an unprecedented legal battle between a small business with under 10 employees and a powerful federal agency that claimed to know better than the consumers it was allegedly protecting. Where working-class black people heard harmless chit-chat, agency officials heard disparaging dog whistles, which their lawsuit said amounted to “redlining.”

Such claims are usually levied at big banks with deep pockets. Townstone marked the first time the bureau, set up in 2010 by Elizabeth Warren, had brought a redlining complaint against a non-bank mortgage lender, which would struggle to afford the multimillion-dollar payouts typical of a settlement with the agency.

It felt like “David and Goliath,” said Barry Sturner, Townstone’s president. And it was happening in a country that ostensibly bars the government from targeting citizens for their speech.

“They twisted innocuous statements about crime into something nefarious and then tried to use it to ruin my reputation and destroy my business,” Sturner said. “When a federal agency with an unlimited budget and army of lawyers comes after your business and smears you as a racist, you’re forced to give in and take it or choose an uphill fight.”

Three years later, Sturner is still fighting. Though a district court dismissed the lawsuit in February, the bureau is now appealing that decision to the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, which could catapult the case to the Supreme Court.

While the odds are stacked against the agency in both venues—the Seventh Circuit, like the High Court, is majority-conservative—the persistence illustrates how government bureaucrats, armed with the mandate of civil rights, can bully and bankrupt businesses for constitutionally protected speech.

Legal fees alone often reach hundreds of thousands of dollars in a case like Townstone’s, said Jessica Thompson, an attorney at the Pacific Legal Foundation, who represented Sturner pro bono. Throw in the possibility of damages, and it’s often safer to settle—a dynamic that allows the government to chill speech merely by opening an investigation and dangling the possibility of a lawsuit.

The result, Thompson said, is a system ripe for constitutional abuses.

“Content- or viewpoint-based restrictions on speech are antithetical to the First Amendment,” she told the Free Beacon. “That means it’s unconstitutional for agency bureaucrats to appoint themselves as speech police to censor discussions on public issues just because they might be offensive to some.”

At least some of that censorship seems to have been due to the cultural distance between inner-city Chicago and Northwest Washington, D.C.

On a 2017 episode of Townstone’s radio show, Sturner referred to a grocery store in the South Side of Chicago, Jewel-Osco, as “Jungle Jewel,” adding that it was “a scary place” with patrons “from all over the world.”

The agency cited the nickname as an example of language that “would discourage” minorities “from applying for credit.” In fact, the jungle moniker has been widely used by black Chicagoans themselves, one of whom told Kleimann Communication Group that Sturner’s comments were “reliable and helpful,” according to the firm’s report.

Other statements the agency cited were blunt but boilerplate. “You drive very fast through Markham,” Sturner said on a 2014 broadcast, referring to a majority-black Chicago suburb that experiences more crime than 95 percent of American cities. “You don’t look at anybody or lock on anybody’s eyes.” On a November 2017 broadcast, a Townstone employee likened the “rush” of skydiving to “walking through the South Side at 3 a.m.”

The agency also chided the hosts for stating, in January 2014, that listeners should “take down the Confederate flag” before putting their homes on the market—guidance that reflects the official policy of the National Association of Realtors, which says displaying a Confederate flag may violate housing discrimination law.

“The Townstone Financial Show has regularly included statements that would discourage African-American prospective applicants from applying for mortgage loans,” the lawsuit said. And its “home-selling advice has included recommendations regarding displays of the Confederate flag.”

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau declined to comment.

It is doubtful that anyone complained to the agency about these statements, said Ted Frank, a well-known conservative attorney who tackles regulatory overreach. Instead, agency officials likely noticed that Townstone made fewer loans in black neighborhoods than others and began poking around.

African Americans only accounted for just 1.4 percent of Townstone’s loan applications between 2014 and 2017, according to the agency’s complaint, and less than 1 percent of its loans were for properties in predominantly black neighborhoods, which comprise around 14 percent of Chicago’s population.

Though such disparities are not illegal in and of themselves—lenders can consider race-blind factors, such as credit scores, that vary on average between racial groups—they can be evidence of discrimination and the catalyst for a lawsuit. The result, Frank said, is a “racial spoils system” in which quotas, while not officially required, are effectively mandatory.

“If you don’t have proportional representation among loan recipients, agencies will look for disparate impact and go after you,” Frank said. “It’s problematic to see Kendism”—a reference to “antiracist” activist Ibram X. Kendi, who argues that all racial disparities reflect racism—”be the official policy of the U.S. government.”

Something like that policy has now been written into the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s operations manual. The bureau said last year that it would sue lenders for disparate impact “regardless of whether it is intentional,” something Congress never authorized it to do.

It was the latest move by an agency that has long taken an expansive view of its mandate, at times interpreting laws to cover far more conduct than their plain text implies.

The Townstone litigation centers on the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which makes it illegal to “discriminate against any applicant” for credit on the basis of race. The agency has interpreted that law to include “prospective applicants” in addition to actual ones—a potentially massive category. It relied on this inflated interpretation to go after Townstone, arguing that the lender could be guilty of discrimination even if it had not discriminated against anyone who had applied for credit.

The argument was so bold that Franklin U. Valderrama, the district court judge presiding over the case, didn’t address the First Amendment issues in his opinion. He dismissed the lawsuit purely on separation of powers grounds, saying the bureau, an Executive Branch agency, had ignored the clear meaning of a congressionally enacted law. For now, it remains an open legal question whether lenders can speak candidly about crime.

The appeal to the Seventh Circuit comes as the bureau’s entire funding structure is under review at the Supreme Court. The existential stakes of that case have stirred debate about how the agency should be reformed and what it is for.

At a congressional hearing in March, Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D., Mass.) answered the second question by pointing to Townstone.

“I for one am glad the agency took action against discriminatory lending practices,” Pressley told the House of Representatives’ Financial Services Committee, citing the company’s “racist messages.” “We need more, not less, of the CFBP.”

Ryan Nevin contributed to this report.

* Article From: The Washington Free Beacon