The plastic barriers that shot up at sales counters and order windows across America during the COVID-19 pandemic may actually be facilitating the spread of the virus, not protecting people from it.

Multiple studies have now shown that the plastic barriers, common everywhere from grocery stores to restaurants to schools, impede air flow and redirect germs from one person to another. Several experts told The New York Times that, in many cases, the barriers provide no protection from COVID-19 and instead make it more likely to spread.

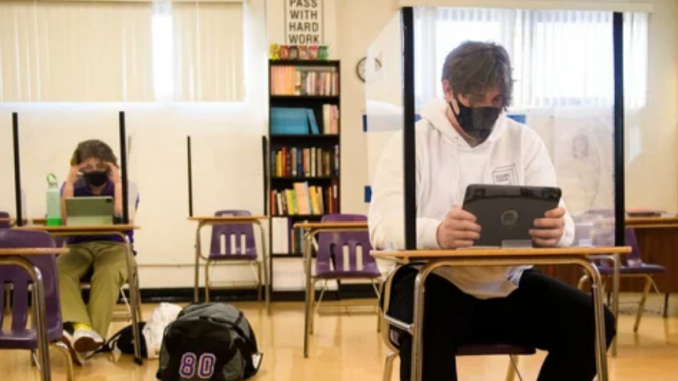

“If you have a forest of barriers in a classroom, it’s going to interfere with proper ventilation of that room,” Linsey Marr, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech, told the NYT. “Everybody’s aerosols are going to be trapped and stuck there and building up, and they will end up spreading beyond your own desk.”

A June study led by researchers from Johns Hopkins University found that plastic screens around desks in classrooms were correlated with increased transmission of COVID-19. Another study of a Massachusetts school district found that the barriers impeded air flow. Scientists say that under normal ventilation circumstances, exhaled virus particles are dispersed and replaced by fresh air every 15 to 30 minutes. With barriers in place that change air flow, dead zones can be created where the fresh air doesn’t travel and the virus particles concentrate.

“We have shown this effect of blocking larger particles, but also that the smaller aerosols travel over the screen and become mixed in the room air within about five minutes,” Catherine Noakes, professor of environmental engineering for buildings at the University of Leeds, told the NYT. “This means if people are interacting for more than a few minutes, they would likely be exposed to the virus regardless of the screen.”

British researchers have found that the plastic barriers are effective at blocking and trapping particles from a sneeze or a cough, hence their use at a place like a salad bar. When it comes to someone simply speaking or breathing, though, the slower particles just float around the barrier, lingering and still threatening store clerks or customers on the other side.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise. Dr. Noakes published a study in 2013 which found that partitions between hospital beds may protect some people from germs, but they direct that dirty air toward others instead. A 2014 study from Australia linked cubicle dividers in an office environment to a tuberculosis outbreak.

“If there are aerosol particles in the classroom air, those shields around students won’t protect them,” incoming engineering dean at the University of California, Davis, Richard Corsi told the NYT. “Depending on the air flow conditions in the room, you can get a downdraft into those little spaces that you’re now confined in and cause particles to concentrate in your space.”

Instead, research indicates, measures like improving ventilation, adding air filtering machines and increasing vaccination rates would do far more to protect people in indoor spaces going forward.

*story by The Daily Caller