(RNS) — When the U.S. Supreme Court was hearing the Obergefell v. Hodges case that eventually made marriage equality a reality across the nation, pagans held rituals on the high court’s steps in Washington.

Led by Firefly House, a local witchcraft community, these public rites called forth the “spirit of justice and revolution” and attracted pagans from around the country. When the decision was finally handed down, the community celebrated.

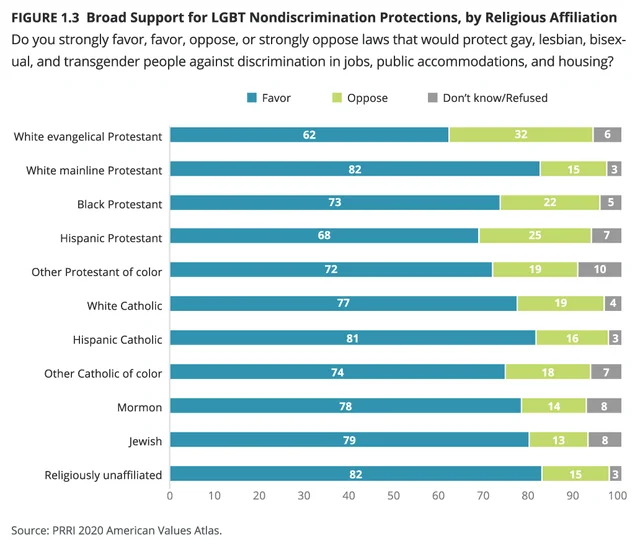

In a recent political profile study, Kathleen Marchetti, an associate professor of political science at Dickinson College, reported that likely 93% of American pagans agree with policies supporting LGBTQ rights, a larger share than the 69% of non-pagans who do. According to a March 2021 PRRI report, the pagan community collectively shows the highest support for LGBTQ individuals of any religious group. The next closest are white mainline Protestants at 82%, followed by Hispanic Catholics at 81%, according to PRRI.

RELATED: ‘Am I the worst thing a person can be?’: Witches fight media bias

Marchetti went so far as to say that support for LGBTQ+ rights was connected to “Pagan religious identity.”

“That sounds about right,” said David Salisbury, a pagan author and LGBTQ+ advocate. “Pagans have always been seen as outliers and oddballs,” which accounts for the level of “empathy expressed,” he said.

“In the 1990s, it was adults creating these spaces and beginning the narratives on these topics. They invited young people to participate,” Salisbury explained. “The pendulum has swung in the opposite direction. Today, the youth are taking charge, especially in online spaces.”

Brianne Raven Wolf, a pagan trans woman and leader of an annual Trans Day of Remembrance ritual, said that when she first openly joined the pagan community, she was “blown away at how accepting it was.”

“When they invite you to sit around the campfire and drink mead, that to me is accepting.”

Some pagan groups have introduced what Salisbury called “queer mythology” into their practice, incorporating deities, such as the Greek god Dionysus, traditionally accepted as queer. In some instances, mythologies and practices that skew toward a heterosexual understanding of sexuality and the world, such as Wiccan god and goddess myths, have been reinterpreted.

These details are crucial to Salisbury’s own religious practice, he said. “Paganism is so experiential that I need to see myself within the spirituality that I’m practicing.”

Clio Ajana, a pagan leader in Minnesota, explained how her group, House of Our Lady of Celestial Fire, known as E.O.C.T.O, has been “a queer haven” since its 1998 founding. “We have always focused on our queer ancestors/ancients, deities, and facilitating those (members) in coming out — especially those who are trans and younger pagans who are just searching.”

Another queer-focused group, the Minoan Brotherhood, calls itself on its website an “initiatory tradition of the Craft celebrating Life, Men Loving Men, and Magic.”

But even pagan groups that aren’t centered on queer practice increasingly make room for LGBTQ people and conversations. Brianne Raven Wolf, a pagan trans woman and leader, said that she has seen more “nonbinary rituals” at pagan events and a growing willingness to talk about diversity and inclusion.

While LGBTQ pagans feel comfortable inside the community, they often feel threatened outside it. Raven Wolf is no longer out as a trans woman or pagan in her local community in western New York state. It is too dangerous. “There is escalating violence. We have to protect our lives,” she said.

And some admit that hostility is not completely absent from the pagan community, despite the high percentage of support.

Lasara Firefox, a nonbinary pagan, told Religion News Service in March that, while there is a “baseline of acceptance in certain sectors of the community,” execution “often doesn’t equal ideals.”

Both Salisbury and Raven Wolf reiterated that the pagan community is still a “reflection of society as a whole.” While rare, problems do arise within some circles and at community events that can leave queer pagans, particularly those in the trans community, feeling isolated, disconnected and even unwelcome. Raven Wolf said the recent political debate over transgender rights has also affected people’s attitudes. She cites the more than 80 anti-transgender state bills proposed just this year. “There is (also) a lot of misinformation online.”

Ajana has also seen the disconnect between ideals and execution, saying that she is “seen as ‘other’ in many spaces.” However, this is not because she is queer but because she is Black. “I can’t separate from my skin color; I have had negative experiences from colorism … first, rather than as a queer person of color.”

Ajana believes that visual representation is one of the biggest problems for queer people of color in the community. If you google pagan, the images will be “overwhelmingly white, mostly female and younger.”

RELATED: Folk healers create modern techniques from their ancestors’ lost lore

“Queer identification is an invisible minority” within that representation. If you google “queer Pagan” she pointed out, you are likely to see mostly white, male authors.

“More consistent visibility equals the slow erasure of feeling invisible within the larger community,” she said. This includes more published works, events at conferences and asking someone’s identity when they register for an event.

However, Ajana, like Raven Wolf, sees reason for hope. “My earliest experiences in the community were very heteronormative; I saw few queer pagans, let alone pagans of color. Now, 17 years later, I am able to find other queer pagans more easily, in part by being visible and making it clear that I am a) queer and b) a queer POC.”

The post Paganism, gods and goddesses aside, is the most LGBTQ-affirming faith in the US appeared first on Religion News Service.

*story by Religion News Service