Allegedly getting almost shoved in front of a train by Brianna Randolph was probably not what a young man standing on the uptown N-Q-R platform was expecting last Saturday morning. But in progressive Gotham, straphangers, pedestrians and ATM customers alike are quickly learning to be ready for anything.

The city’s leadership privileges violent and mentally ill perpetrators over the safety and security of ordinary New Yorkers – the ones who never assault strangers, defecate in public or throw garbage cans in the street.

It would be one thing if the perpetrators were all random one-offs, people who one day just snapped. But as was the alleged case with Randolph, a large number of frightening street assaults are committed by people who have had multiple interactions with law enforcers, the mental-health establishment or both.

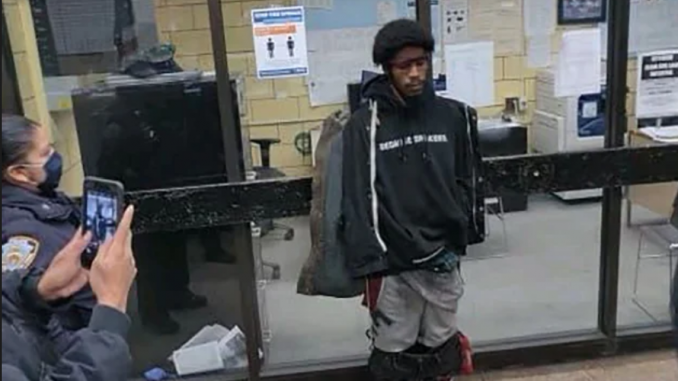

Randolph is a prodigious victimizer, having been arrested seven times in a few weeks, six times for assault and once for grand larceny. Each time, she was booked and arraigned, then sprung.

This sort of thing is common, and often leads to dire results. Randy Santos murdered four homeless men in Chinatown one night in October 2019, after having been arrested several times earlier that year for the “minor” offenses of forcible touching and fare evasion; his case was diverted into a “supervised release” program that he never showed up for.

Rigoberto Lopez attacked four people, killing two, in a stabbing spree this February. Lopez had multiple arrests for violent assaults and drug offenses and was also released under supervision, which he ignored. CASES, the social-service provider that Lopez was supposed to answer to, reported his noncompliance, but his case was never followed up.

A hardcore cohort of maniacs menace the city. They are known to authorities through their long careers of low-level-but-escalating criminality. But it seems that until these individuals murder someone, nothing is done to get them off the streets.

It’s a scandal. Part of the problem is that the city has adopted a model of dealing with chronic offenders that more closely resembles customer service than law enforcement. The rhetoric on street homelessness exemplifies this approach.

“Individuals living on the street face tremendous barriers to coming indoors,” the Department of Homeless Services explains. But those “barriers” have nothing to do with extensive paperwork, proof of need or an invasive interview process – it’s simply that the homeless people in question don’t want to get help with their drug addiction or mental illness. Hence, “it can take months of persistent and compassionate engagement, involving hundreds of contacts, to successfully encourage street homeless individuals to accept city services and transition indoors.”

By this customer-oriented logic, when homeless people continually reject “persistent and compassionate engagement,” the only correct response is to figure out how to make the offer more attractive: letting them inject drugs safely, allowing them to bring their pets into shelters and so on.

A similar approach is adopted in regard to “diverting” criminals from incarceration. Jail, it is commonly accepted, is an awful consequence of terrible life choices. But advocates have taken that to mean that we must do everything we can to keep thugs and gangsters on the streets, regardless of cost. Public Advocate Jumaane Williams – who lives within the secure confines of a US army base – speaks about the “significant stress” that being arrested can cause.

Under Mayor Bill de Blasio and the ascendency of progressives to power in the Big Apple, “alternatives to incarceration” have become the gold standard of criminal jurisprudence. ATI may have their place in a toolbox of punitive options, but the city has adopted the same placating client-service approach with criminals as it takes with the homeless.

For instance, the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice’s “practice guidelines” for ATI advise, “Many people are not prepared to make substantial life changes when they are recommended to participate in a treatment program or services.” It is thus “incumbent upon treatment providers to appropriately craft motivation to build individuals’ self-confidence in the possibility and potential benefits of change.” ATI must “focus on individuals’ willingness, readiness and interest in engaging in services.”

One would think that not having to go to jail would be “motivation” enough to engage willingly in a cognitive-behavioral therapy program. But no. As long as New York City continues to treat its criminal deviants as wayward toddlers in a Montessori setting, we are going to continue having violent, unchecked individuals act out their rages on a docile populace.

*story by The New York Post